Accessibility and Usability at Angelo.edu and Their Effects on Students with Disabilities

Jeff Caldwell

Department of English and Modern Languages

Angelo State University

Abstract

The U.S. federal government requires that all Title IV higher education institutions comply with specific web accessibility guidelines (WCAG) v2.0 (Taylor. 61.). Nevertheless, many schools have failed to build affordances for students with disabilities into their websites, as evidenced by the more than 8,000 digital accessibility lawsuits filed against schools in federal courts between 2017 and 2020 (Vu et al.). In addition, more students with disabilities are choosing distance learning (Mullin et al. 6.). As a result, schools that fail to adhere to strict accessibility standards face an increased risk of litigation.

Through a combination of automated software tests and the subjective input of students with disabilities, this research reveals that several student-facing pages on the Angelo State University (ASU) website fail to meet accessibility standards and that those failures negatively affect students with disabilities and their ability to locate important information, register for courses, and manage their student accounts.

Introduction

Definitions of web accessibility have varied throughout the history of the web; however, providing an accessible and usable experience to users with disabilities has been considered essential since the platform’s early development (World Wide Web Consortium, 1997). The most popular definition, according to an industry survey (Yesilda et al., 2012), was put forth by the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), which states, “Web accessibility means that websites, tools, and technologies are designed and developed so that people with disabilities can use them” (Web Accessibility Initiative, 2023). WAI further specifies that accessibility dictates that users should be able to perceive, understand, navigate, interact with, and contribute to the web (Web Accessibility Initiative, 2023). While this definition focuses on users with disabilities, the International Standard Organization (ISO) offers a broader perspective, defining accessibility as “the extent to which products, systems, services, environments and facilities can be used by people from a population with the widest range of user needs” (International Organization for Standardization, 2021). Together, these examples show that concepts of accessibility overlap with concepts of usability, which focus on how efficiently, effectively, and satisfactorily a user can complete tasks with a given application or website (World Wide Web Consortium, 2016).

As time has passed, accessibility guidelines have come to include suggestions that incorporate usability concepts (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0, n.d.). However, there remains a lack of evidence that conformance to these guidelines leads to more usable websites for people with disabilities (Power et al., 2012, p. 433). One study conducted at the University of New York states that Success Criteria did not cover up to 49.6% of difficulties faced by users in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (Power et al., 2012, p. 438). The study suggests that adherence to WCAG guidelines may be a potentially beneficial component for designing and developing inclusive websites, but conformance alone does not guarantee that a website will be accessible for users with disabilities.

This paper presents a study that answers the following empirical questions:

- To what extent do student-facing pages at Angelo.edu conform to WCAG 2.0 guidelines?

- To what extent do the accessibility and usability of those pages affect students with vision and mobility disabilities?

For the purposes of this study, the term “student-facing pages” refers specifically to web pages on the university website that provide critical functionality and services for current students. These include pages and portals that enable enrolled students to complete key administrative tasks such as registering for courses, accessing academic records and transcripts, managing financial aid, and tracking degree progress.

This research evaluated web accessibility barriers that impact users with vision disabilities through an approach that incorporated multiple methods. Automated accessibility audits measured compliance with technical guidelines that benefit those using screen readers, while an in-person usability study enlisted student participants with vision disabilities to complete common tasks using assistive technologies. Their feedback provided critical insights into real-world challenges not fully addressed by guideline compliance alone.

Additionally, while mobility disabilities were not necessarily represented among the test subjects, all encountered interaction difficulties stemming from reliance on keyboard rather than mouse input for navigation. By focusing analysis on both standards compliance and representative users who predominantly depend on keyboard control, this study aimed to uncover obstacles across key populations who face accessibility and usability challenges in web environments.

Quantifying violations and qualitatively showcasing struggles provides Angelo State administrators with actionable insights that prioritize beneficial remedies for current and prospective students. The choice by administrators to embed inclusiveness into protocols surrounding the design and implementation of critical service infrastructurerepresented by the website would signal a meaningful commitment to addressing systemic barriers for disabled users over checklist compliance. While additional progress would remain imperative, self-initiated auditing would signify awareness and willingness to incrementally enhance accessibility. This user-informed approach, combined with roadmaps for remediation lessens the potential exposure should legal threats materialize.

Method

Design

The study was conducted in two stages, designed to collect quantitative data about the number of WCAG 2.0 violations on the student-facing pages of the university website and the effect of WCAG 2.0 conformance on blind or partially sighted subjects. The first stage gathered quantitative data by analyzing selected pages using the Axe Core automated accessibility testing tool (Axe-Core, 2023). Axe Core’s reports reported the number of WCAG 2.0 violations per page and the level of anticipated impact per error. The second stage gathered qualitative data through task-based user evaluation with vision-disabled student subjects on selected pages. Subjects were asked to perform four tasks designed to represent student interactions with the core services provided by the page.

Pages scanned

A total of 29 web pages were scanned using the Axe Core testing software. Those pages were segmented for analysis according to their location and their provided functionality. Web pages fell into two primary categories: 1) Seven pages that consisted of outward-facing content geared toward prospective students, parents, visitors, and other external site traffic. These pages were publicly available without the need for authentication. 2) 22 pages that enabled students to perform critical administrative functions in areas such as registration, financials, academics, and access to campus life. These pages required university authentication for access. Pages that provided core student services were further segmented by functionality and overall page structure and were categorized as A) RamPort — the portal through which students access information about academics, registration, financial aid, and campus life, B) Banner Self Service — the portal used by students to interact with university systems such as admission, class registration, and bill payment.

Participants

Usability testing was performed with a purposive sample of three ASU students with vision disabilities. Subjects were recruited with the assistance of the Director of Student Disability Services. While the small number of participants does not shed light on the percentage of the student population who might share the same experiences with the website, their feedback provides valuable qualitative insights into the barriers faced by similar students. The three subjects are referred to as Subject 1, Subject 2, and Subject 3 throughout the report to maintain anonymity while allowing clear distinction of feedback by each individual. Participants each had some degree of vision disability and provided feedback according to their experience. A description of each subject is provided in Table 1.

| Pseudonym | Description |

|---|---|

| Subject 1 | A first-year remote student who lost their sight in 2006. Participated remotely via video conferencing software with screen-sharing. |

| Subject 2 | A legally-blind student who attended class on-campus. Was unable to use a screen-reader, however disability required significant text magnification. |

| Subject 3 | A student who lost vision in one eye. Simulated blindness for this study through the use of an eye-covering. |

Quantitative measures: automated accessibility testing

Automated testing was performed by using a custom-coded web crawler that navigated to selected web pages with a “headless browser” provided by the Playwright end-to-end testing suite (Fast and Reliable End-to-End Testing for Modern Web Apps | Playwright, n.d.), and used Axe Core to run automated accessibility tests. Axe Core is an open-source automated web accessibility testing library (Axe-Core, 2023). It contains accessibility rule implementations that can programmatically check any web page or application against the latest web accessibility guidelines (WCAG). A headless browser is a web browser without a graphical user interface that can be controlled programmatically. These browsers enable automated testing by simulating user interactions and rendering content without the visible interface of a normal browser. They provide support for web standards and run browser engines internally so they can access web content like a typical browser.

Scoring metrics

Tests performed by Axe Core produce reports that detail the number of WCAG 2.0 violations on a page and assign one of four impact levels to accessibility issues - minor, moderate, serious, and critical. Minor issues cause frustration but do not prohibit access. Moderate issues impede some users from completing certain workflows. Serious issues partially or fully block access to crucial content and functions for assisted technology users. Critical issues entirely prevent users from utilizing essential site capabilities. For this study, issues were assigned a point value according to their impact level. Table 2 shows the scores assigned to each accessibility violation.

| Impact | Point Value |

|---|---|

| Critical | 20 points |

| Serious | 10 points |

| Moderate | 5 points |

| Minor | 1 point |

Scores were then calculated for each page by summing the total values of all issues on the page. Cumulative scores were then divided into five categories, listed in Table 3. Overall page category scores were applied as an average of all individual page scores.

| Point Value | Accessibility Level |

|---|---|

| 100+ | Extremely low accessibility |

| 50-99 | Very low accessibility |

| 25-49 | Moderately low accessibility |

| 10-24 | Somewhat inaccessible |

| Under 10 | Mostly accessible |

Qualitative measures: usability testing

Subjects were asked to complete four tasks of varying levels of difficulty within the span of a one-hour usability testing session. Each task was designed to represent a typical situation in which a student needed access to important information or services offered by the website. To prevent unwanted changes to a subject’s account or registration status, subjects were asked not to submit or submit any forms they successfully filled out. The tasks, in the order they were presented to subjects were:

- You are a new student at Angelo State. Find and complete the “MyAccount” form to start at ASU. Do not submit the form when you’re done.

- You have forgotten your password. Find and fill out the MyPassword password reset form. Do not submit the form when you’re done.

- You have signed up for a minor in Journalism. Find a course in the spring of 2024 that fulfills a requirement for the minor and register for the course.

- You are considering applying to a graduate program at Angelo State. Find a program that interests you, then navigate to your unofficial transcripts to verify whether you meet the requirements.

Results and key observations

Automated testing results

Over the 29 pages that were scanned, 16 pages fell under the “Banner Self Service” category, six were categorized under “RamPort,” and seven were categorized as “Other” and represented the public-facing pages of the website. A total of 116 accessibility violations were detected, a mean of 4 violations per page. Errors with moderate impact represented the largest impact category among all errors, with 72 reported (Table 4).

| Metric | Banner Self Service | RamPort | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Violations per Page | 3.31 | 8.5 | 1.71 |

| Total Violations | 53 | 51 | 12 |

| Minor Violations | 2 | 6 | 7 |

| Moderate Violations | 44 | 23 | 5 |

| Serious Violations | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Critical Violations | 7 | 10 | 0 |

| Mean Accessibility Score | 23.56 | 73.5 | 4.57 |

| Accessibility Level | Somewhat Inaccesibe | Very Low Accessibility | Mostly Accessible |

While the highest number of violations belonged to the Banner Self Service category, that group also represented the largest set of pages that were scanned — well over twice as many as either of the other two groups. The mean number of errors per page within Banner Self Service was 3.31. RamPort, with only six pages scanned, had only two fewer errors than Banner Self Service, giving the category a mean of 8.5 violations per page. Other pages had the fewest violations, with 12 total errors and a mean violation per page of 1.71 (Figure 1).

Automated testing shows that RamPort carries the highest number of WCAG violations per page. The category also has the highest number of critical violations — ten in total — and represents the only category with at least one violation of every impact type. If accessibility compliance were the only factor that decided a student’s ability to navigate a page and benefit from its services, RamPort would represent the most imposing digital obstacle facing disabled students.

Because RamPort had the highest average number of violations per page, this study will highlight some of those with the most detrimental impact on users. The following violations represent a small selection meant to serve as an illustrative example, not a comprehensive enumeration of the violations found across the site or their impact on students.

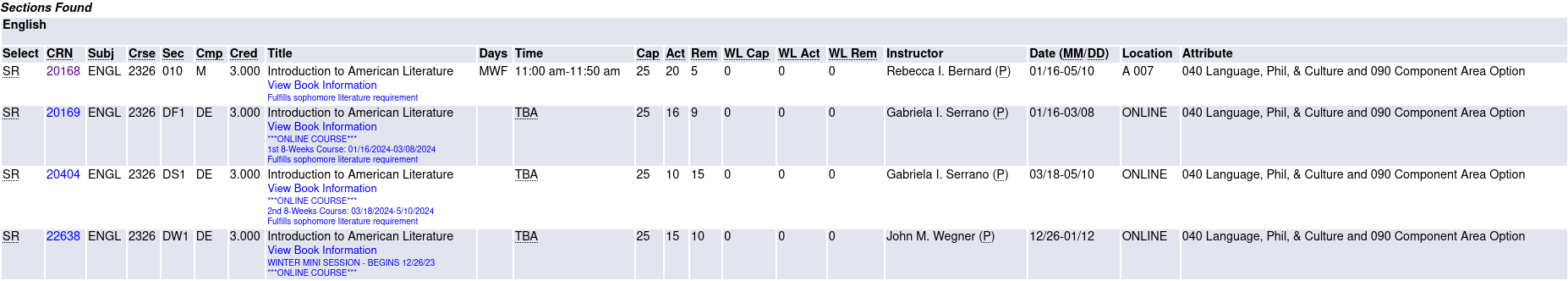

Five reported violations, the majority of those reported on each RamPort page, originate from the sidebar menu (Figure 2). A violation is generated for each of the five links within the menu because, while each element includes an appropriate ARIA role “(WAI-ARIA Roles - Accessibility | MDN, 2023) — “menu-item” — those elements are not contained by a parent element with an appropriate “menu,” “menubar,” or “group” role. While reporting five violations for something that can be corrected by editing a single element may seem misleading, the consequences for keyboard-dependent users merit the associated level of urgency.

The “menu” and similar roles signal to screen readers that the user who navigates to the list of links or actions is now interacting with a menu and, with proper labeling, allows them to either skip past the enclosed items or through them one by one (Menu and Menubar Pattern — Initiative (WAI), n.d.). When the appropriate ARIA role is missing, it forces users to navigate through every menu link without indicating that they are in a menu. In the case of RamPort, users perform this list cycling before they reach the primary content on the page. To make matters more complex, any time a user navigates to another page in the RamPort category, they must repeat the cycle. This repetitive, time-consuming, and sometimes strenuous interaction erodes a user’s precious time and may lead to discomfort, pain, or a feeling of exclusion (Stories of Web Users — Initiative (WAI), 2023).

Usability testing results

Within a one-hour usability testing session, subjects were asked to complete four tasks that involved interacting with at least one of the three primary page categories. Task 1, which required subjects to interact with pages in the Other category, took an average of eight minutes to complete per user. Task 2, which also required students to interact with the Other category, took an average of six minutes per user. Task 3, which required users to interact with the RamPort and Banner Self Service categories, took an average of 35 minutes per user. None of the users could complete Task 4 within the testing period (Figure 3). While Task 3 is included in the average time per task results, only one student, Subject 3, was able to complete the task without assistance successfully.

Discussion and analysis

Over the course of usability testing, several patterns emerged that may help illuminate barriers faced by students with disabilities. Consistent issues experienced by all three participants may provide insight into obstacles impacting a broader range of users. Of special interest is the fact that subjects spent relatively little time navigating RamPort while completing Task 3. This suggests that, while RamPort accounted for the highest number of accessibility violations, subjects faced relatively few usability problems when using the page. Instead, subjects spent the most time trying to navigate and understand the Banner Self Service class lookup table (Figure 4). The class lookup table consists of 20 columns of information that users must navigate one cell at a time in sequence because of how screen readers operate. In testing, every subject expressed frustration at the difficulty of understanding where they were on the page, with one student summarizing the table as “an abundance of interaction,” and “absolutely overwhelming.”

It should be noted that Subject 3, the only subject to complete the registration task without assistance, was the subject who simulated blindness through the use of an eye-covering. The subject suggested that their ability to complete the task was largely because they could approach the class lookup table with a previously constructed mental model from having seen it before the test. Neither Subject 1 nor Subject 2 had ever interacted with the lookup table before testing, and both stated that they instead enlisted outside assistance to register for classes.

During debriefing interviews, most subjects expressed a preference for or desire to complete tasks like class registration without the need for outside assistance. Subjects who preferred this autonomy suggested that their negative experiences while interacting with student-facing pages were the primary reason for needing assistance. The most specific feedback came from Subject 1, who stated, “I have to tab through everything and try to keep in mind where I’m at, so it was just easier to have my advisor do it.”

Recommendations

To rectify the obstacles faced by students with disabilities, this study suggests a number of remedies that range from relatively simple adjustments to the underlying UI code to more challenging but necessary usability testing. It’s understood that staff at ASU may not have access to the source code of vendor-provided portals. However, these guidelines may help administrators choose the product that offers the greatest level of inclusivity for all students.

Technical fixes

A large number of the accessibility violations reported in this study could be rectified by changes in the HTML structure that would take relatively little time. With the assistance of free accessibility tools and browser extensions, staff developers should be able to adjust pages like RamPort so they more closely comply with WCAG 2.0 guidelines. The following suggestions are only partial, as a comprehensive listing of every issue and how to correct it is outside the scope of this document. What follows is a set of what the researcher believes are the smallest changes that will have the largest accessibility impact with the smallest investment in time or effort on the part of university staff.

- RamPort

• The majority of reported accessibility violations stemmed from the structure of the sidebar navigation menu. Using a

<nav>tag with proper aria role would correct five of the critical violations reported on all RamPort pages. • The page’s primary content should be placed within a<main>element, and that element should reside at the top level of the document. • All color combinations in the document should be tested using an automated testing tool and adjusted for acceptable color contrast - Banner Self Service

• Headings should follow proper heading order, and there should be at least one

<h1>per page. • The page’s primary content should be placed within a<main>element, and that element should reside at the top level of the document. - Other

• Alt text for images should be descriptive and should not be repeated by image captions.

• Navigation menus, such as the “breadcrumb” navigation menu at the top of many public-facing pages on the ASU site (Figure 5), should be contained within a “landmark” element such as

<main>or<header>(HTML5 Landmark Elements Are Used to Improve Navigation | Lighthouse, n.d.).

Usability testing

Once adjustments are made to bring the site closer to accessibility standards, an effort should be made to assess the usability of the student-facing pages on the site with special care devoted to those pages that represent critical functionality for users.

One major pain point observed in testing was the class registration lookup page. Its multi-column, densely packed table layout caused considerable confusion and slow parsing, even among experienced users. To alleviate this issue, an alternative organization focused first on class schedule availability followed by a clean, clearly tagged section for each class’s details merits exploration. For example, leveraging a more judicious heading hierarchy and simplifying the volume of data presented simultaneously could aid comprehension. However, further testing is required to determine the optimal structure and presentation before overhauling any page.

Conclusion

This study into the accessibility and usability of student-facing web pages at Angelo State University clearly reveals deficiencies that inhibit usage by students with disabilities. RamPort’s higher violation severity risks excluding visually and motor impaired students from vital academic interactions and could potentially expose the university to litigation.

Observed usability challenges with intricate, overwhelming interfaces like the course registration page confirm that WCAG standards fail to address usability barriers alone. Students require inclusive universal access that meets both technical guidelines and real usability needs. Prioritizing fixes that target navigation and comprehension promises an improved experience for users in the short term. However, long-term, institutional commitment to user research is required to ensure the best experience for all users.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the College of Graduate Studies and Research for the opportunity to conduct this research, to Dr. Dallas Swafford for her assistance in finding participants, to the ASU IT Department for providing secure access to RamPort, to my mentor, Dr. Kevin Garrison, for his guidance and insight, and to the students who volunteered their time.

References

ARIA menu role—Accessibility | MDN. (2023, November 14).

Axe-core. (2023, September 21). NPM.

Fast and reliable end-to-end testing for modern web apps | Playwright. (n.d.).

Giraud, S., Thérouanne, P., & Steiner, D. D. (2018). Web accessibility: Filtering redundant and irrelevant information improves website usability for blind users. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 111, 23–35.

HTML5 landmark elements are used to improve navigation | Lighthouse. (n.d.). Chrome for Developers.

Initiative (WAI), W. W. A. (2016, May 6). Accessibility, Usability, and Inclusion. Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI).

Initiative (WAI), W. W. A. (n.d.). Menu and Menubar Pattern. Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI).

Initiative (WAI), W. W. A. (2023, December 13). Stories of Web Users. Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI).

ISO 9241-20:2021(en), Ergonomics of human-system interaction—Part 20: An ergonomic approach to accessibility within the ISO 9241 series. (n.d.).

Mullin, C. (2021).ADA Research Brief: Digital Access for Students in Higher Education and the ADA. ADA National Network Knowledge Translation Center.

Power, C., Freire, A., Petrie, H., & Swallow, D. (2012). Guidelines are only half of the story: Accessibility problems encountered by blind users on the web. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 433–442.

Taylor, Z. W. (2019). Web (In)Accessible: Supporting Access to Texas Higher Education for Students with Disabilities. Texas Education Review, 7(2), 60–75.

Vu, M., Launey, K., & Egan, J. (2022). The Law on Website and Mobile Accessibility Continues to Grow at a Glacial Pace Even as Lawsuit Numbers Reach All-Time Highs. Law Practice: The Business of Practicing Law, 48(1), 1–6.

WAI-ARIA Roles—Accessibility | MDN. (2023, September 27).

Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), W. W. A. (2023, November 20). Introduction to Web Accessibility. Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI).

World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Launches International Web Accessibility Initiative. (1997, April 7). W3C.

Yesilada, Y., Brajnik, G., Vigo, M., & Harper, S. (2015). Exploring perceptions of web accessibility: A survey approach. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34(2), 119–134.